Our research interests are always changing and evolving, as they should! Below, we’ve included brief snapshots of topics that represent primary themes in our ongoing research. However, our interests are broad and not limited to just these areas! Visit our publications page for a more comprehensive look at the research we’ve been involved with. Please feel free to reach out if you are interested in learning more.

Ecology and conservation of forest wildlife in fire-prone ecosystems

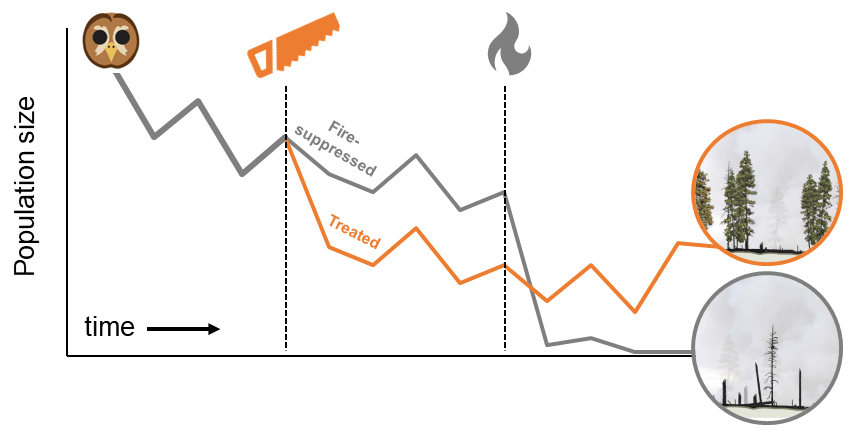

Fire is an important agent of change in ecosystems all over the world. However, because of fire suppression, land development, and global warming, humans have changed the nature of how fires burn. Now, in some parts of the world, fires burn bigger and hotter than they used to, and this poses new challenges for both people and for wildlife that are not adapted to these new fire regimes. We conduct research on wildlife responses to fire, and also wildlife responses to forest management actions that are intended to reduce fire severity (e.g., tree thinning) and increase ecosystem resilience.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., H. A. Kramer, W. J. Berigan, S. A. Whitmore, R. J. Gutiérrez, M. Z. Peery (2021) Megafire causes persistent loss of an old-forest species. Animal Conservation 24: 925-936.

Ayars, J., H. A. Kramer, G. M. Jones (2023) The 2020 to 2021 California megafires and their impacts to wildlife habitat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120: e2312909120.

Jones, G. M., M. A. Clément, C. E. Latimer, M. E. Wright, J. S. Sanderlin, S. J. Hedwall, R. Kirby (2024) Frequent burning and limited stand-replacing fire supports Mexican spotted owl pair occupancy. Fire Ecology 20: 37.

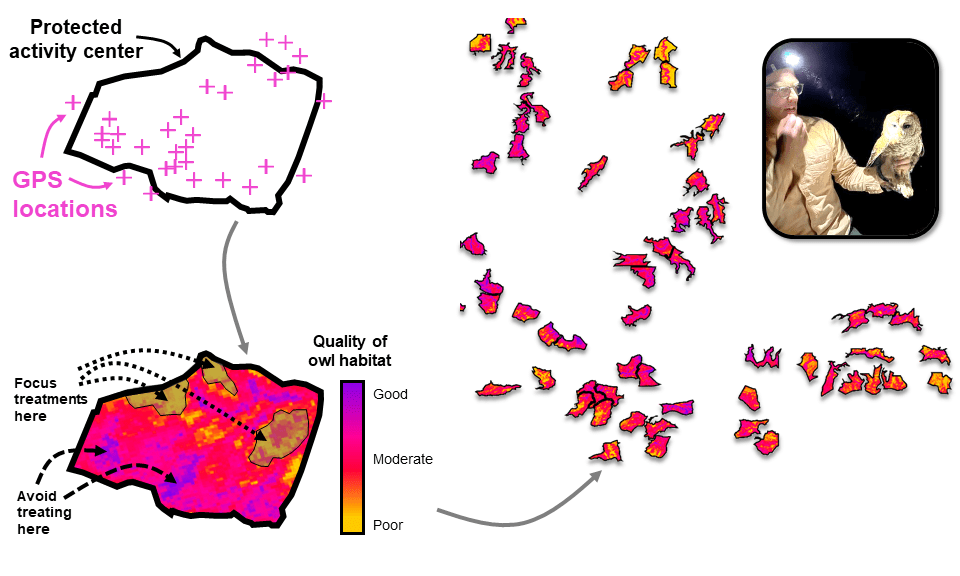

“Living maps” of wildlife habitat for conservation planning

Our world is changing rapidly. The increasing prevalence of mega-disturbances like fire and drought, the ratcheting effects of climate change, and human development and resource use are transforming landscapes before our eyes. Land managers, policymakers, and scientists alike need to better understand how these changes are affecting our natural resources. Using the power of Google Earth Engine, we develop ‘living maps’ that allow managers to understand the effects of disturbances on wildlife habitat in near-real time. These tools allow continual tracking of change, so that land managers never have out-of-date information on the location of species habitat.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., A. J. Shirk, Z. Yang, R. J. Davis, J. L. Ganey, R. J. Gutiérrez, S. P. Healey, S. J. Hedwall, S. J. Hoagland, R. Maes, K. Malcolm, K. S. McKelvey, J. S. Sanderlin, M. K. Schwartz, M. E. Seamans, H. Y. Wan, S. A. Cushman (2023) Spatial and temporal dynamics of Mexican spotted owl habitat in the southwestern US. Landscape Ecology 38: 7-22.

Hart, R.*, C. M. Thompson, J. M. Tucker, S. C. Sawyer, S. A. Eyes, S. J. Saberi, Z. Yang, G. M. Jones (2025) Rapid declines in southern Sierra Nevada fisher habitat driven by drought and wildfire. Diversity and Distributions 31: e70023.

Shirk, A. J., G. M. Jones, Z. Yang, R. J. Davis, J. L. Ganey, R. J. Gutiérrez, S. P. Healey, S. J. Hedwall, S. J. Hoagland, R. Maes, K. Malcolm, K. S. McKelvey, C. Vynne, J. S. Sanderlin, M. K. Schwartz, M. E. Seamans, H. Y. Wan, S. A. Cushman (2023) Automated habitat monitoring systems linked to adaptive management: a new paradigm for species conservation in an era of rapid environmental change. Landscape Ecology 38: 23-37.

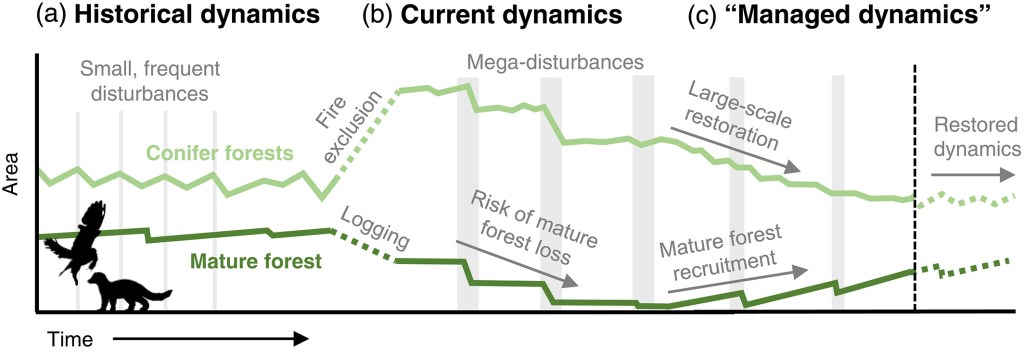

Conservation paradigms in dynamic landscapes

The protected area paradigm forms the backbone of modern conservation. However, the current policies and practices in protected areas reinforce a static view of nature. This view is further enabled by cultural resistance to change, including efforts to mitigate or exclude keystone ecosystem processes (e.g., characteristic wildfire) that create and maintain desired conditions. This protectionist model of conservation undervalues the human role in generating landscape dynamics and will be ineffective over the long term and increasingly in the short term. Within protected areas, there is an urgent need to rethink what we are protecting: the current landscape conditions or the landscape dynamics that generate those conditions.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., C. Thompson, S. C. Sawyer, K. E. Norman, S. A. Parks, T. M. Hayes, D. L. Hankins (2025) Conserving landscape dynamics, not just landscapes. BioScience 75: 409–415.

Steel, Z. L., G. M. Jones, B. M. Collins, R. Green, A. Koltunov, K. Purcell, S. C. Sawyer, P. Stine (2023) Mega-disturbances cause rapid decline of mature conifer forest habitat in California. Ecological Applications 33: e2763.

Gaines, W. L., P. F. Hessburg, G. H. Aplet, P. Henson, S. J. Prichard, D. Churchill, G. M. Jones, D. J. Isaak, C. Vynne (2022) Climate change and forest management on federal lands in the Pacific Northwest, USA: managing for dynamic landscapes. Forest Ecology and Management 504: 119794.

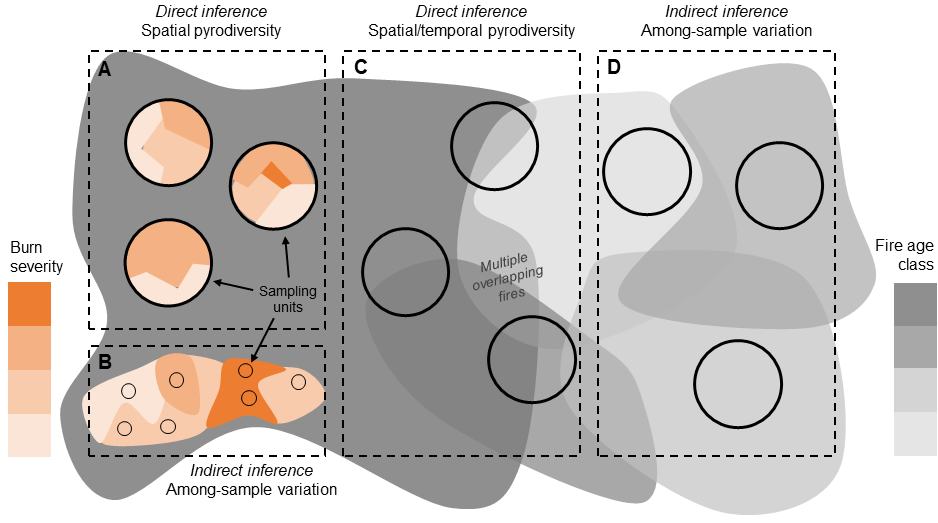

The pyrodiversity-biodiversity hypothesis

Several fundamental ecological hypotheses predict that biodiversity will be maximized in landscapes with greater environmental heterogeneity, because greater heterogeneity offers a broader breadth of niches for different species to occupy. Fire is a major driver of landscape variation, and therefore, a prediction has emerged that areas experiencing greater “pyrodiversity” (that is, greater heterogeneity in burn characteristics) will support higher biodiversity. Our work seeks to understand the mechanisms underlying the pyrodiversity-biodiversity hypothesis and its implications for conservation and fire management.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M. and M. W. Tingley (2022) Pyrodiversity and biodiversity: a history, synthesis, and outlook. Diversity and Distributions 28: 386-403.

Steel, Z. L., J. E. D. Miller, L. C. Ponisio, M. W. Tingley, K. Wilkin, R. V. Blakey, K. M. Hoffman, G. M. Jones (2024) A roadmap for pyrodiversity science. Journal of Biogeography 51: 280-293.

Jones, G. M., J. Ayars, S. A. Parks, H. E. Chmura, S. A. Cushman, J. S. Sanderlin (2022) Pyrodiversity in a warming world: research challenges and opportunities. Current Landscape Ecology Reports 7: 49-67.

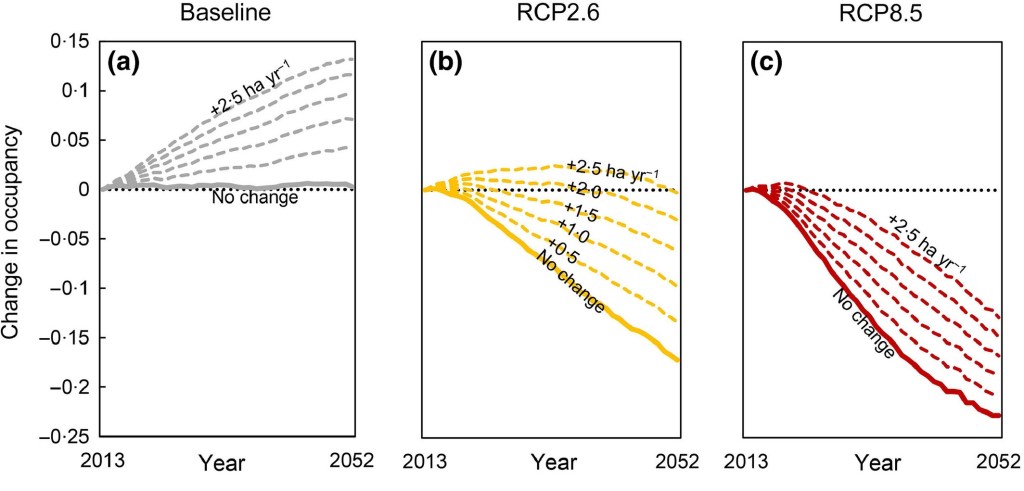

Strategies for wildlife conservation in a changing climate

Climate change is affecting species and their habitats in ways that alter how we think about conservation. We conduct research that helps uncover the diverse ways wildlife respond to climate change and how we can manage lands to mitigate negative impacts. To do this, we use models that link variation in wildlife population processes (e.g., colonization or extinction dynamics) to environmental conditions under future climate scenarios. Of particular interest is uncovering interactions between effects of climate and land cover on population processes.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., R. J. Gutiérrez, D. J. Tempel, B. Zuckerberg, M. Z. Peery (2016) Using dynamic occupancy models to inform climate change adaptation strategies for California spotted owls. Journal of Applied Ecology 53: 895-905.

Jones, G. M., B. M. Collins, L. E. Hankin, R. Hart*, M. D. Meyer, J. Regelbrugge, Z. L. Steel, C. Thompson (2025) Collapse and restoration of mature forest habitat in California. Biological Conservation 308: 111241.

Jones, G. M., A. R. Keyser, A. L. Westerling, W. J. Baldwin, J. J. Keane, S. C. Sawyer, J. D. J. Clare, R. J. Gutiérrez, M. Z. Peery (2022) Forest restoration limits megafires and supports species conservation under climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 20: 210-216.

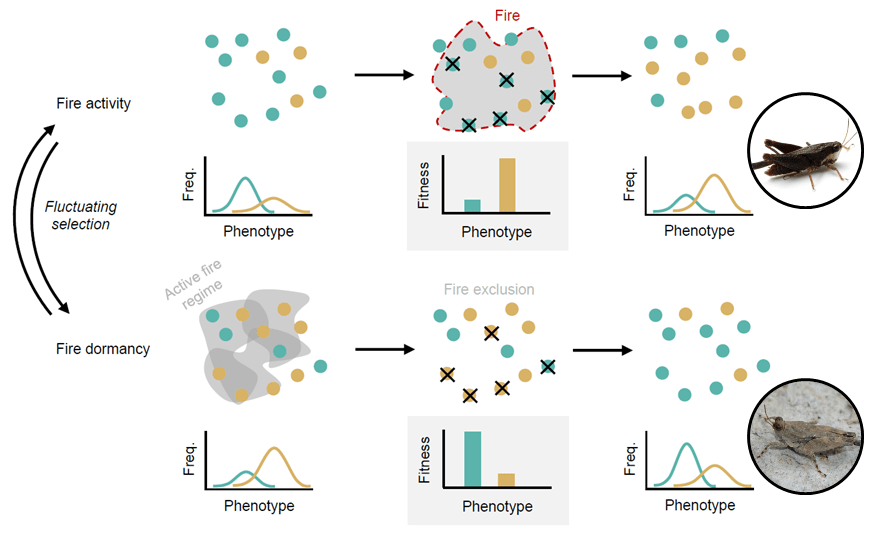

Evolutionary adaptations to fire regimes in animals

Fire is a major selective force in terrestrial ecosystems, and life on Earth has accumulated adaptations to survive fires and persist in burned landscapes. In plants, such traits are widely known – such as thick bark, serotiny, vegetative re-sprouting, etc. However, in animals, fire adaptations are less understood. Our work seeks to understand the breadth of fire adaptations in animal life, how rapidly changing fire regimes may influence evolution, and the implications of fire-driven evolution for conservation.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., J. Goldberg, T. Wilcox, L. Buckley, C. L. Parr, E. B. Linck, E. D. Fountain, M. K. Schwartz (2023) Fire-driven animal evolution in the Pyrocene. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 38: 1072-1084.

McGinn, K., C. J. Zulla, M. E. Wright, Z. Wilkinson, B. P. Dotters, K. N. Roberts, J. J. Keane, M. Z. Peery, G. M. Jones (2024) Energetics explain predator occurrence and movement in pyrodiverse landscapes. Landscape Ecology 39: 182.

Jones, G. M., H. A. Kramer, S. A. Whitmore, W. J. Berigan, D. J. Tempel, C. M. Wood, B. K. Hobart, T. Erker, F. A. Atuo, N. K. Pietrunti, R. Kelsey, R. J. Gutiérrez, M. Z. Peery (2020) Habitat selection by spotted owls after a megafire reflects their adaptation to historical frequent-fire regimes. Landscape Ecology 35: 1199-1213.

Informing conservation through animal movement ecology

The way that animals move across landscapes gives us information about what environmental features are important to them. With emerging high-resolution GPS technologies, our ability to discern fine-grained movements by animals can help us better understand their spatial habitat ecology and inform targeted land management for conservation. We use animal movement models (e.g. resource- and step-selection functions) to understand the role of individual variation, landscape configuration, and environmental gradients in mediating resource selection by animals.

Example publications:

Jones, G. M., D. S. Reid, C. J. Zulla, J. Williams, S. J. Hedwall, R. Kirby (2025) Mexican spotted owls use forest mosaics affected by timber harvest, insects, and wildfire. Southwestern Naturalist 69: 1-8.

Zulla, C. J., G. M. Jones, H. A. Kramer, J. J. Keane, K. N. Roberts, B. P. Dotters, S. C. Sawyer, S. A. Whitmore, W. J. Berigan, K. G. Kelly, R. J. Gutiérrez, M. Z. Peery (2023) Forest heterogeneity outweighs movement costs by enhancing hunting success and fitness in spotted owls. Landscape Ecology 38: 2655-2673.

Kramer H. A., G. M. Jones, V. R. Kane, B. Bartl-Geller, J. T. Kane, S. A. Whitmore, W. J. Berigan, B. P. Dotters, K. N. Roberts, S. C. Sawyer, J. J. Keane, M. P. North, R. J. Gutiérrez, M. Z. Peery (2021) Elevational gradients strongly mediate habitat selection patterns in a nocturnal predator. Ecosphere 12(5): e03500.